About six months after I started my job, I mentioned to my mentor that what worried me was knowing that I was the worst developer on the team. She told me that I was definitely not.

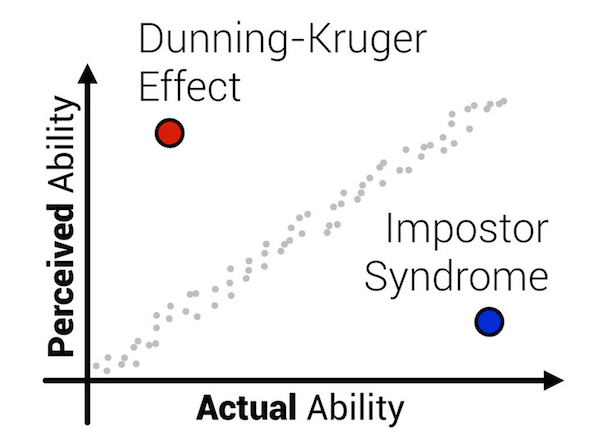

People are often bad at judging how good they are at things. At one end of the scale we have the Dunning-Kruger effect, in which people who aren’t particularly good at something mistakenly believe their level of skill to be very high; people who are incompetent rarely recognize this. At the other end, people who are skilled at a given task tend to find it easy, assume that others also find it easy, and thus tend to underestimate their own skills; after all, they’re only good at easy tasks!

Computer programming is such a complex task, with new things constantly needing to be learned, that it’s very easy to feel like you’re falling behind. Then you look at your coworkers, who don’t appear to be having any particular difficulty, and feel like you’re not good enough to deserve the position you’re in.

When I confessed to one of the senior developers on the team that I didn’t really feel like I knew what I was doing, he said he also felt that way during his first year, which made me feel better about my situation. After my first year, I still felt a little out of my depth, but the feeling of “I have no idea what’s going on!” had gone away.

The turning point for me was shortly after my second year with the company. The coding metrics we use showed that my performance was in line with the rest of the developers, and I got a sizable raise. This was when I started to relax. I figured, based on the raise, that my employer thought I was doing a good job, so I could probably stop worrying about getting fired because I didn’t know what I was doing.

Being a programmer means constantly failing at things; you never seem to feel fully competent (or at least, after five years, I still don’t). Of course, when you’re just starting, the feelings of inadequacy are natural; without experience, you really aren’t particularly competent yet! But when it comes to programming, those feelings may never go away because you never feel like you’re caught up.

One thing that stuck with me last year, when I heard Bob Martin speak, was he mentioned that the number of programmers doubles every five years. That means that, even though I had very little practical experience when I started my job five years ago, I’m now more experienced than half of the developers out there! Additionally, my job is not static – I have to do new things all the time, which means constant frustration but also constant learning. A few days ago, it occurred to me to think about it mathematically: if I’ve improved my skills by 2% each month, then I’m twice as good as I was three years ago. Of course, if it’s hard to measure how good people are at programming, it’s likely going to be even harder to measure improvement, but if you can find some sign each month that you’re a better programmer than you were the month before, you’re probably on the right track.

And if you were competent three years ago and you’re twice as good now, then you’re probably not terrible at this after all.

What really made me start to feel that maybe I actually know what I’m doing, is when I realized that the newer developers have been asking me a lot of questions and I’ve actually been able to answer most of them.