When I first started as a developer, the process was simple. You picked (or were assigned) a bug to fix, you fixed it, and then you sent it off for testing.

…and then, sometimes, your tester (another developer) argued that you’d fixed the bug in entirely the wrong way and should completely redo the fix. Sometimes he also provided information you didn’t know about that proved he was definitely correct.

Then we added a design requirement. Before doing a fix, you had to have another developer sign off on what you were going to do, which meant that many potential problems could be uncovered before putting in too many hours of work.

Of course, it wasn’t always that easy. Sometimes you don’t have any idea how to fix a problem until you’ve spent a while working on it, and sometimes you just have to sit down and code a solution before you know whether it’ll work or not. But overall, adding a design step to the process made it flow a lot more smoothly, even taking the additional design time into account.

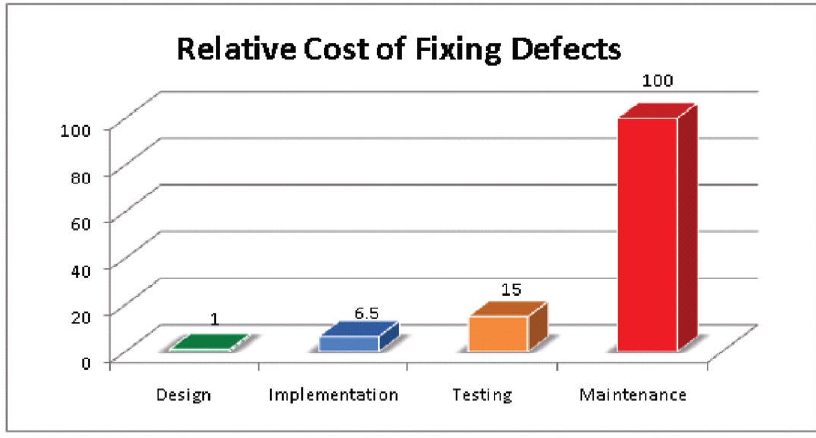

No doubt you’ve seen infographics similar to this one:

The idea is simple: the earlier a problem is found, the easier it can be fixed. It’s easy to move lines around in a blueprint; it’s much more difficult to move the walls in a finished building. Similarly, it’s best to get input from all the stakeholders as to whether your proposed fix meets their needs before you actually spend a lot of time implementing and testing it, especially if it takes a while for new development to make it through the testing process. We actively solicit feedback from end users before a new feature is complete, because we want to know how it meets their needs while we’re still building, not a year later when we’ve moved on to other things.

Of course, it’s also easy to go too far. A design shouldn’t be a copy of all the code changes you’re making (unless it’s a really simple change); in that case you’re still doing the development first and getting feedback later. At the same time, it should usually be more detailed than “there’s a bug in this part of the code and we’re going to fix it.” At minimum, as a person reading your design, I should understand:

- What is the problem?

- How are you doing to fix it?

- How will I know it’s been fixed?

For example, a design might be something like:

- When you do X, the software crashes.

- This happens because we didn’t check for a null property before accessing a subproperty, in this function.

Pretty straightforward, right? But it’s clear what the problem is (the software crashes), what the developer is going to do about it (add a null check), and what the result will be (the software will no longer crash). The technical reviewers understand what the fix will be and can suggest changes (should we be showing an error message if that property is null?). The testers understand the workflow they have to follow to reproduce the crash (or rather, to not reproduce it). And the poor developer doesn’t have to make the fix, test it, send it off for code review, and then be told to do something completely different. Everybody wins!